I flicked the TV on last week in time to catch the end of I Remember Mamma with Irene Dunne. In case you haven’t seen it, it’s the story of a Norwegian immigrant family in San Francisco in the early 20th century. The mother, Marta is instrumental in her daughter Katrin’s writing career. In so many movies women played minor roles, and yet these women were strong beyond measure, and determined for their children to succeed. Just as my mum was. Not all women are conquering the world by running big businesses. Many of them are conquering the world by providing strong shoulders for their children to climb upon. That’s what Mothers do.

My parents were big movie fans and when an old movie came on the TV Mum and Dad would say. “You’ll really enjoy this.” And when, 90 minutes later we were sobbing our little hearts out at The Yearling with Gregory Peck or Random Harvest with Ronald Colman and Greer Garson , Dad would say that that was a good thing. It showed you had feelings, showed you had heart. Dad had a big heart. He loved people, loved music, loved film – and he loved us. Most importantly of all, he loved my mum.

I grew up in Cleethorpes, a small seaside town on the east coast (UK) that sits next to Grimsby, once the largest  fishing port in the world. There were plenty of stories there, one on every corner, only I didn’t realise that then. I didn’t think great stories could be about ordinary people, the people I would meet on the streets of my home town. I thought it was ‘small town ordinary’, nothing like the places I saw in films or on TV. Yet no place is really ‘small town, ordinary’ – it’s the people that make it interesting, the people who create the stories by living them.

fishing port in the world. There were plenty of stories there, one on every corner, only I didn’t realise that then. I didn’t think great stories could be about ordinary people, the people I would meet on the streets of my home town. I thought it was ‘small town ordinary’, nothing like the places I saw in films or on TV. Yet no place is really ‘small town, ordinary’ – it’s the people that make it interesting, the people who create the stories by living them.

My maternal Grandmother, Nanny Lettie used to tell me stories all the time. Not sit me on your knee, bedtime stories with a beginning a middle and an end; they were the stories of her family. A walk from her house in Dugard Road, onto Queen Mary Avenue then to Park Street, past the Clee Park, Susan’s Cakes, the Fishmongers, all the way along to the seafront in Cleethorpes, was the story of life and how she dealt with it. Depending which way we walked she would tell me who lived in which house, where the cinema had been, who married who, who was on what ship…and so on. Many of those stories stayed with me. Most especially was the one she told often, of when her brother’s ship, the steam trawler Leicestershire, was lost with all hands off the Old Many of Hoy in the Orkneys in 1938. Alf was 25 years old. Fifteen men died leaving 23 children fatherless. What did the women do then?

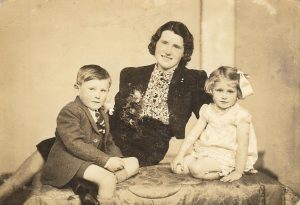

Nanny said that was the first real shock in her life, that it hurt so bad she thought she would never get over it. Three years later she was widowed when my grandfather was killed in the war. She was left with two small children – my uncle aged 6, my mother 4. After that, she said, each disaster didn’t knock her off her feet. It’s not that she didn’t feel the pain, it’s that she learned that life goes on, that she could survive. And she did, scars and all. She survived, and her survival taught me that I could too. Whatever life threw at me I would recall Nanny Lettie and find some of her strength to get me through to the next part of my own story.

Nanny said that was the first real shock in her life, that it hurt so bad she thought she would never get over it. Three years later she was widowed when my grandfather was killed in the war. She was left with two small children – my uncle aged 6, my mother 4. After that, she said, each disaster didn’t knock her off her feet. It’s not that she didn’t feel the pain, it’s that she learned that life goes on, that she could survive. And she did, scars and all. She survived, and her survival taught me that I could too. Whatever life threw at me I would recall Nanny Lettie and find some of her strength to get me through to the next part of my own story.

The first article I ever wrote was about the Leicestershire. I wrote it to read at a writers’ group I belonged to at the time. I sent it to my mother who, unbeknown to me, sent it to the local pape r. They published it a few weeks later. I was thrilled, my first success. Of course that first heady rush of confidence and self-belief soon subsided and the doubts rushed in. They were being kind, it was a fluke. It took me years of getting published to even begin to call myself a writer. I may never have started if it hadn’t been for my mother, quietly in the background, giving me wings.

r. They published it a few weeks later. I was thrilled, my first success. Of course that first heady rush of confidence and self-belief soon subsided and the doubts rushed in. They were being kind, it was a fluke. It took me years of getting published to even begin to call myself a writer. I may never have started if it hadn’t been for my mother, quietly in the background, giving me wings.

So, don’t leave it too long to tell your story, don’t think that it’s too small town ordinary. If it hadn’t been for my mother perhaps I would have never

taken those first steps. Mothers everywhere are encouraging their children, every minute or every day. Life’s ordinary heroines. We owe them so much.